Pancho Guedes can be best described as a meteor. He exploded brilliantly, landed in an inhospitable and exotic place, created surprise and amazement, sent shock waves amongst academics and specialists and then, as often happens, he was slowly forgotten, between the transformation of memory into myth and the progressive abandonment of his scattered physical traces.

Those who nowadays visit Maputo, former Lourenço Marques, can still discover these traces – now appropriated by the population, and disfigured by history but, yet, still ready and willing to show the resistance and grace which only an adaptive architecture is able to offer.

Within the international specialist circles, only a few still remember the phenomenon and repercussions that he generated.

Pancho Guedes thus remains as a shining and exceptional moment, which along with a few others throughout the 20th Century reverberates with the echoes of a history that could have been shaped in a different manner.

However, history reassesses itself and sometimes recaptures its lost moments and, as such, the memory and consequences of the impact of Pancho Guedes are once again the subject of interest and curiosity.

The echoes of the period are thus restored; the archaeological remains are analysed; new are established; and, enfin, historical continuity is reshaped through the logic of the exceptional event.

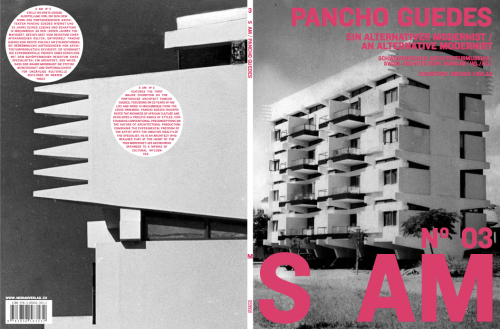

SAM exhibition entrance view…

As he himself was fond of saying, in 25 years Pancho Guedes built enough to fill a medium-sized city. This effervescent activity took place in Mozambique – a remote location improbable in terms of Eurocentric and western standards – between 1950 and 1975, while the world was euphorically growing towards the fall of economic and cultural modernity as it had been known until then.

There, this Portuguese-born architect, raised and trained in Africa, produced an eccentric and idiosyncratic oeuvre, which during the 1950s alone would guarantee him a place in the irregular history of the exceptions to the most canonical architectural Modernism.

As Simon Sadler and Timothy Ostler demonstrate elsewhere in these pages, the work of Pancho Guedes can naturally be charted in terms of its influences, contexts and connections – and this involves the rediscovery of architectural attitudes and values which history frequently insists on forgetting or obliterating.

Besides this mapping, however, the creative melting pot rediscovered in the work of Pancho Guedes also reveals that his meteoric character contained some prophecies with regard to the destinies of western modernity.

Pancho’s personality and path thus speak to us not only of the occasional alternatives to architectural modernism soon recognisable in the post-war period, but also prefigure the progressive revision of some traumas and idiosyncrasies enclosed in the idea of modernity.

Along with a few other singular and meteoric characters, Pancho Guedes is thus one of the most enlightening mid twentieth century proto-postmodernists.

Pancho Guedes’s architectural influences, for example, belong to a line of modern references that range from Horta to Gaudi or from Wright to Le Corbusier.

In each one of these masters, Pacho sought the organic aspects, which were opposed to the more rationalist trends of the Modern Movement.

Similarly, he found his most cherished sources for inspiration within the artistic universes of Expressionism, Surrealism or Dada.

Amongst these links, his voracious and open appetite for information and his artistic vocation created the conditions for an untypical creativity.

On the other hand, the contexts in which Pancho moved can be divided between the cultivated atmosphere of modernism’s first questionings – present in South Africa’s architectural milieu – and the hybrid multicultural environment of a colonial city experiencing a sudden and fairly chaotic growth.

The contradictions between these two universes created the conditions for the ironic and ludic attitude with which Pancho would refute formulaic and homogeneous answers to the challenges usually faced by architects.

Whilst his colleagues coming from Portugal were looking out for colonial Africa as an opportunity and a free range to experiment with a modernism repressed by the motherland’s Fascist regime, Pancho was already far ahead, exploring the crossroads of contrasting cultural universes.

Meanwhile, the connections which Pancho would establish with the wider architectural world – his closeness to Bruce Goff or his joining of Team 10, the recognition of both Reyner Banham and André Bloc – will confirm that his work and attitude are, in any event, difficult to classify and unify, even within the scope of the most radical revisions of modernity.

Team 10, for example, fully welcomed his energy, dynamism and critical sharpness, but ultimately some of its members will show difficulties in accepting his vibrant and provocative eclecticism.

In a similar manner, his successful reception in specialist circles at the end of the 1950s was brilliant but fleeting, and the most explicit – or most subconscious – appropriations of his inheritance would be reserved for the 1960s Pop and utopian architecture, for the 1970s and 80s Post-Modernists or even for the Blob architecture and Retro-Futurism of the 1990s.

As it happened with Goff and a few others, the uniqueness of Pancho Guedes’ creative mix would ultimately ensure the continuity of a specific formal and spatial approach to architecture. And although clearly in the minority during the Modern Movement, this approach still corresponded to one of the fundamental aspects of modernity at large: its expressionistic, baroque and organic side.

Within the architectural universe, Pancho Guedes was, as such and par excelence, a true alternative modernist. Besides this, however, his work also shows premonitory echoes of an alternative modernity that, in essence, is the one we are immersed in nowadays.

In its most wide-ranging cultural dimension, the work of Pancho anticipates various returns which characterise a time which perhaps, rather than post-modern, should really be called alter-modern.

During International Style’s hegemony, Pancho’s architecture announced the return to stylistic diversity as a creative strategy and even as a response to the needs of the system of consumption.

It was not by chance that Pancho Guedes’s varied architectural styles provided an answer to the variety of needs and conditions specified by clients and circumstances.

With Pancho, we are in Africa facing situations of great economic and cultural imbalance, with no unified or coherent style which could possible respond to this state of affairs. We are, at the least, between two worlds and, with the exception of an imposed colonial regime, there was no western modernism capable of offering a single answer to this reality, which has remained contradictory to this day.

Pancho found an alternative to the exhaustion of models produced by a uniformising modern culture amongst his more personal styles, but also in ironically addressing the most limited and archetypical aspirations of the recipients of his work.

From the intelligent utilisation of local techniques and abilities to the acceptance of basic economic conditions, Pancho Guedes opened the path to an architecture which was truly contextual and multicultural.

In this sense, Pancho genuinely anticipated a form of critical regionalism which, however, was also understandably unclassifiable within the critical reading which this trend would come to have through Keneth Frampton. In fact, Pancho’s work just as easily undoes the ideological trigger which transformed critical regionalism into a new definition of style, this one full of late-modern minimalist connotations which also become quite restrictive.

The stylistic diversity of Pancho Guedes’s work – transformed in a classificatory fever which reminds one of the innocence of the 17th and 18th Centuries anthropological discoveries – deludes the consensuses over a style which seeks to represent the unity and imposition of western modernity.

In this sense, the work of Pancho directly alludes to that which had to be repressed in modern culture so as to obtain its widened consensus and dissemination.

Pancho Guedes’s oeuvre fully anticipates the so-called return of the repressed and this can be explained by a number of specific factors.

Firstly, Pancho experienced the relative isolation and freedom of the African continent in the 1950s.

Since what was repressed here was clearly colonial in kind, that which is repressed never fully disappears.

As Michel de Certeau could suggest, the repressed is actually irrepressible in a colonial regime, it rather remains present in cultural differences that are impossible to amalgamate.

Working within the periphery’s informality, Pancho embraced and superimposed these differences and started to produce a stylistic detour which would have been unacceptable in a context – the centre – where the policing of the borders of the repressed was more evidently at work.

There were obviously channels of communication between the African periphery and the centre and Guedes was particularly zealous about the information he received and consumed, constantly arriving at him from the major centres.

However, since the information Pancho consumed was mainly mediated, he also anticipated a very contemporary phenomenon: the mediation ensured a critical distance, a vision of the whole, which frequently is lost in the centre itself.

Cultivated, perspicacious and open, Pacho would in his own way recognise the small hegemonies which were actually manufacturing modernism’s standardisation.

In his irreverent manner, Pancho would then react, as Alison Smithson as put it, with “a laughter in his voice.”

In his laughter Pancho exposed a certain naïve quality, but also he displayed a cultivated irony that would actually allow him to break out from the repressed.

From the empathy to the magical primitivism which surrounded him in Africa to the free exploration of the unconscious which came from the Surrealists; between the freedom offered by a noncritical atmosphere and his own worldly and open cosmopolitanism, Pancho brought together unique characteristics, which enabled him to temporarily free himself from modernity’s rationalist aura.

Between Picasso and Freud, between Lourenço Marques and London, Pacho went back to the childhood of modern culture and, with the liberty of one who is aware of its unconscious and traumas, just projected it onto the future.

The artistic freedom which Pancho Guedes reclaims for his architecture leads him to a time before his own – to a moment where the guidelines of modernity were still fully blooming – and, at the same time, throws him to that future in which the so-called post-modern would, basically, unveil a return to the scattered and repressed roots of modernity.

All of this occurred during a relatively short period, during the 1950s, before Pancho himself would become embroiled by rationalist economics and the formal limitations of his own modernity.

But this brief moment was sufficiently intense to guarantee Pancho Guedes a fixed place in the history of 20th Century architecture.

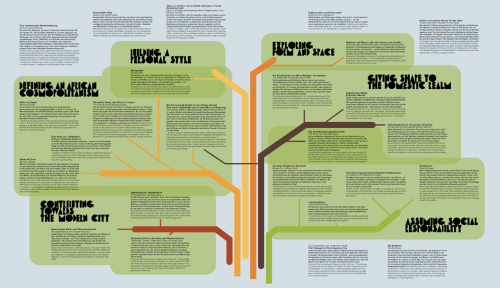

A tree of styles: the six lines within the exhibition…

In its most exuberant and expressive character, Pancho’s architecture thus merrily escapes the moral task to which architectural modernism had consciously and diligently dedicated itself: the exclusion of the symbolic, the rejection of ornament, and the repression of the eclectic.

In his discovery of African cultural diversity, Pancho welcomed the symbolic and ritualistic dimension of material culture, along with the animism of surfaces and forms. He allowed himself the freedom to play with whatever architectural languages he finds more suitable.

In his own “Stiloguedes,” Pancho thus combines the rationalism and structural rigour of western culture with the magical and organic dimension of African symbology.

What, at the beginning of the modern, had been condemned as a crime – ornament – thus returns as a symbolic dimension which was practically lost in western architecture. And what was the purpose of that symbolic dimension? Simply to offer references for the creation of identities and, after all, to offer grounds for an appropriation of architecture that, meanwhile had dissipated in the midst of this discipline’s specialisation.

Since architecture’s specialisation had been transformed into a style, it was also through style that Pancho offered the way to invert this trend.

His eclectism thus emerges not as the stylistic confusion which over the 19th Century had been the cause of the first proto-modernists’ despair, but as a way of relearning the possibilities of architecture’s many languages.

As Picasso had classically suggested, after the specialisation’s learnings, it is necessary to unlearn them so as to enable a fully creative language, one which is truly suitable to the expressive needs of both creator and consumer.

Precociously, Pancho Guedes has indeed taken on board an eclectism which within the mid 20th Century modernist regime made him persona non grata – except along with those who were also seeking alternatives to the rationalisation and uniformisation of modernity of which Henri Lefébvre has spoken.

Finally, in his hybridisation of cultures, Pancho Guedes has further suggested another important return: the return of the Other.

Immersed in the culture of western culture’s true Other – that whose repression goes together with a major part of European modernity’s growth – Pancho Guedes is one of the first to open himself to African culture and put into question the certainties of Eurocentric culture.

Just like an anthropologist who cannot avoid loving the object of his or her attention, Pancho is influenced by the charms and magical aspects of African culture and, as such, breaks with the structuralist aura of his own culture. The Other becomes the distorting mirror on which the pristine self-image of western culture shatters.

In view of this evidence, it is appropriate that it is us who should now return to Pancho Guedes.

September 2007, published in “Pancho Guedes, an Alternative Modernist” catalogue, S AM, Basel. Published here on occasion of Pancho’s retrospective in Lisbon, May 2009.

Pingback: Pancho Guedes: Story of an Exhibition « shrapnel contemporary

Pingback: Pancho Guedes